Ogun at a Crossroads: Obasanjo’s Rebuke and the Senator Adeola Question

By Muyiwa Sobo

When I first watched that video, which had since gone viral, I was immediately reminded of what the late Dr. Christopher Kolade once said at his 80th birthday celebration. Responding to a toast from the former president, his longtime friend, Dr. Kolade, confessed, with gentle humor, that he was often apprehensive whenever Chief Olusegun Obasanjo rose to speak. You never knew what would come out of his mouth. That unpredictability was on full display again at the much-celebrated 50th anniversary of Ogun State’s creation. With the now widely circulated line, “Awon Aremo to ja’le l’Eko …,”former President Obasanjo delivered what many have described as a brutal political takedown, a campaign slogan, characteristically sharp, layered, and impossible to ignore.

Interpreted broadly, the remark has wide application. There are several “Aremos” in Ogun State, by lineage, residence, or association, who live in Lagos or have strong ties to it.

But context and language matter. In Yoruba usage, particularly in political rhetoric, the word “ole”(thief), when used colloquially, does not necessarily imply a legal finding of theft. It does not mean that any Aremo has been formally adjudicated a thief or convicted of stealing in Lagos. Rather, it can function as a pointed moral or political rebuke, sharp, metaphorical, and deliberately provocative.

As Dr. Kolade suggested, when Obasanjo speaks, one listens carefully not only to what is said but also to what is meant.

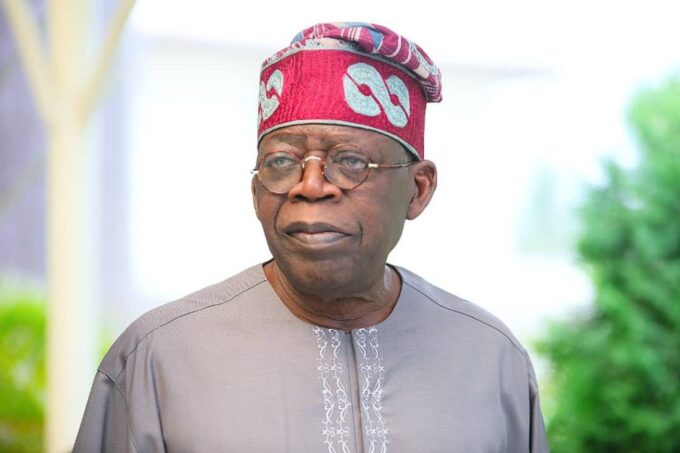

That statement landed squarely on the chest of Senator Olamilekan Adeola’s gubernatorial ambition. The senator representing Ogun West and Chairman of the formidable Senate

Appropriations Committee was reportedly reduced to tears by the sting of that public rebuke. Adeola is no political lightweight. A hardened “Lagos boy” forged in the rough-and-tumble politics of Alimosho, armed with deep pockets and widely seen as an ally of the current president, he did not stumble into Ogun politics by accident. He executed a calculated political migration.

Leveraging money, influence, and strategic alliances, he effectively bent the political architecture of Ogun West to accommodate his transition from Lagos powerbroker to Ogun senator, clinching the seat vacated by Senator Dada. His cross-border ascent was neither organic nor incidental; it was engineered. And in a political environment sensitive to questions of identity, loyalty, and territorial legitimacy, the former president’s remark did not float in abstraction. It struck at the heart of a carefully constructed ambition.

In Lagos, Senator Adeola confronted a political reality he could not overcome: the road to the governorship was effectively closed. The power structure rooted on Lagos Island was entrenched, territorial, and tightly coordinated—unwilling to surrender control to a Mainland aspirant regardless of ambition or financial muscle. It was a machine that could not be bullied, bought, or bent. Faced with that wall, he did not dismantle his ambition. He redirected it.

Blessed with a name that carries no immediate territorial stamp within Yorubaland, Adeola could conveniently assert indigeneity wherever it proved politically useful. When Senator Dada exited the Ogun West senatorial seat, and the argument for rotational equity began to favor Ogun West, producing the next governor after Governor Dapo Abiodun of Ogun East, Adeola saw his opening.What followed was not chance; it was strategy. With money deployed to cultivate local power brokers and carefully assembled alliances, he planted roots in Ilaro, erected symbols of belonging, and asserted indigeneity.

From there, he captured the Ogun West senatorial seat, less as an end in itself and more as a launchpad. The objective was clear from the outset: to secure a foothold in Ogun politics, consolidate influence, and position himself to contest the governorship. It was a political relocation executed with calculation, capital, and cold ambition.

With decades of political instinct and hard-earned battlefield experience, Obasanjo recognized the play immediately. He saw the calculations, mapped the alliances, and grasped the ultimate objective. And at the symbolic moment of Ogun State’s 50th anniversary, he delivered his warning.

To Obasanjo, this was not ordinary political maneuvering. It was an attempted takeover, an effort to secure Ogun State through ambition amplified by financial force. He cast it as a state in danger of being auctioned off to satisfy the governorship aspirations of a political transplant, an outsider in his view, seeking to capture a prize that had not been earned through organic roots or long-standing investment in the state’s political life.

In Obasanjo’s telling, Ogun is no ordinary state to be captured through maneuver and money. It is a state with a fierce political heritage, a cradle of nationalist struggle, intellectualism, and institutional memory. Handing it over to satisfy the ambition of one individual, however powerful, If Nigeria possesses a political conscience, Ogun State has frequently been its clearest expression.

It is the homeland of formidable Yoruba polities – the Egba, Ijebu, Yewa, Remo, and Awori –communities that mastered the art of governance and resistance long before Nigeria was conceived as a nation.

Well before amalgamation, the people of Ogun were already negotiating authority, confronting domination, and asserting their right to self-rule. That legacy of political awareness and defiance has not faded; it continues to reverberate through some of the most defining moments in Nigeria’s national story.

Abeokuta, the Ogun State capital, was not merely a settlement; it was a fortress of independence.

The Egba’s resistance to colonial control revealed a political culture that questioned authority rather than submitting to it. This refusal to bow easily to power became Ogun State’s defining political inheritance.

That inheritance later produced a disproportionate number of Nigeria’s most influential figures. Chief Obafemi Awolowo reimagined governance around education and social welfare. Chief M.K.O. Abiola paid the ultimate price for a stolen mandate. Shonekan stood tall when summoned. Obasanjo ruled Nigeria twice, in uniform and in civilian garb, shaping the country’s democratic transition. These were not accidental outcomes; they were products of a state steeped in political consciousness.

Abeokuta, the state capital, was never just a town on the map; it was a citadel of defiance. The Egba resistance to colonial intrusion was not passive hesitation; it was organized, principled opposition. Authority was questioned, not worshipped. Power was scrutinized, not blindly obeyed.

That instinct to challenge rather than capitulate became Ogun State’s enduring political DNA.From that tradition emerged an outsized share of Nigeria’s defining figures. Obafemi Awolowo did not merely participate in politics; he redefined governance through education and social welfare. M.K.O. Abiola bore the cost of a stolen mandate with historic consequences. Ernest Shonekan stepped forward in a turbulent national moment. Olusegun Obasanjo led Nigeria twice, first in uniform, then in civilian attire, leaving an indelible mark on the country’s democratic trajectory. These were not coincidences of birth. They were the natural outgrowth of a state steeped in political awareness, intellectual rigor, and a stubborn refusal to bow to power without question.

Ogun State has repeatedly stood at the fault lines of Nigerian politics. The June 12 crisis was not merely an electoral disagreement; it was a profound national rupture, crystallized around the mandate of an Ogun son. In that moment, the state became both a beacon of democratic aspiration and a reminder of what the country failed to defend: the sanctity of the ballot and the will of the people.

Yet Ogun’s narrative is not one-dimensional. For all the thinkers, reformers, and martyrs it has produced, the state has also embodied the very contradictions it often critiques – entrenched elite influence, uneven development, and episodes of political betrayal. That duality makes Ogun less a sanctified pedestal and more a revealing mirror, one that reflects Nigeria’s strengths and shortcomings alike.

Geographically and politically adjacent to Lagos, Ogun now occupies a strategic intersection of power, commerce, and ambition. Its posture—whether assertive or acquiescent—carries weight beyond its borders. When Ogun takes a stand, it resonates nationally; when it hesitates, that too sends a message. Nigeria’s political story, therefore, cannot be told with integrity without Ogun State.

It is a place where ideas have confronted authority, where democracy has paid a price, and where the nation is repeatedly compelled to examine its own unresolved failures.

It is against this historical and political backdrop that the governorship ambition of Senator

Olamilekan Adeola must be examined. The issue before Ogun State is not whether Adeola understands politics; he does. Nor is it whether he commands influence in Abuja; he clearly does.

The real question is more fundamental: should Ogun entrust its highest office to a politician whose deepest roots, enduring loyalties, and long-term political investments were cultivated elsewhere?

Ambition, however vigorous, is not the same as organic leadership. Adeola’s political ascent was built in Lagos State, particularly in Alimosho, where his networks, alliances, and identity were established over the course of decades. His emergence in Ogun was not the product of sustained grassroots demand from within the state. It followed a strategic reassessment when the pathway to the Lagos governorship narrowed beyond reach.

Leadership is strongest when it grows from shared struggle, consistent presence, and community immersion, not from strategic relocation. Ogun State should not serve as an alternative platform for ambitions that encountered structural limits elsewhere.

Ogun State has a distinct political history—one defined by ideological struggle, intellectual leadership, and principled resistance. From Awolowo to Abiola, Ogun’s politics has always had a philosophical backbone. It has never been merely transactional.Allowing a Lagos-centered political structure to replicate itself in Ogun risks reducing the state to a satellite arena for external political interests. Ogun is not an annex. It is not a spare room in Lagos’ political house.

Constructing a residence in Ilaro and asserting local belonging does not automatically translate into deep community integration. Political legitimacy is earned over time through sustained presence, service, and cultural alignment—not through rapid relocation powered by financial leverage. Ogun West deserves a governor whose roots are intertwined with its history, not one whose presence is recent and strategically timed.

By the way, a fundamental question demands a direct answer: when Senator Adeola was building his political empire in Alimosho, what exactly did he state as his place of origin in his party registration documents? It certainly was not Ilaro. It could not have been Ilaro. No political structure in Alimosho would have embraced, nurtured, and repeatedly elected a man who openly declared another state as his political home.

From the Lagos State House of Assembly to the House of Representatives and ultimately to the Senate, Adeola rose through Lagos politics as a Lagos politician. That ascent was not accidental—it was rooted in declared affiliation and accepted identity. You cannot spend decades presenting yourself to Lagos voters as one of them, secure their mandates at every level, benefit from their structure, and then pivot overnight to claim deep ancestral belonging elsewhere when ambition requires it.

Political identity is not a seasonal garment. It cannot be worn in Alimosho for twenty years and then swapped for Ilaro when the governorship equation changes. The record matters. And the question remains: where did he say he was from when it counted?

As this debate unfolds, a brazen mob of political parasites and career sycophants, men and women with no spine and no shame, whose existence depends on scavenging from the banquet of power, have already staged a premature coronation of Adeola as the APC’s gubernatorial candidate. Their arguments are as hollow as their loyalty. First, they flaunt Adeola’s reckless cash-splashing across every ward and village as if democracy were an auction.

Second, they mutter about a so-called presidential anointment, as though Nigeria has quietly abandoned elections for imperial decrees.

Let’s be clear: money politics is corruption in ceremonial dress. It is decay masquerading as strength. And while some may treat the rumored presidential blessing as sacred and unquestionable, the more disturbing reality is the widespread belief that Adeola’s rise in Ogun

West, and now his gubernatorial ambition, has been built not on organic support or earned credibility but on relentless spending and high-level political patronage. Any serious APC stakeholder who values institutional survival should be alarmed, not only for the party’s integrity but for the catastrophic signal it sends to an opposition eager to weaponize this excess and finally break the APC’s grip on the state.

When political dominance is bought with torrents of cash and cemented through federal proximity, especially through opaque access to public funds meant for citizens, democracy does not merely weaken; it is systematically dismantled. It breeds a culture of dependence, silences internal dissent, and turns party structures into bidding floors. And it provokes a blunt, unavoidable question, at least from those not scrambling for handouts: what is the true source of the staggering sums underwriting this political conquest? Adeola’s professional life, by every observable measure, has been overwhelmingly political.

The official salary and allowances of a senator are public record.

What is not public, however, is the depth of influence and financial latitude attached to chairing the Senate Appropriations Committee, and how easily that leverage can be twisted into a pipeline for illicit accumulation, funding a political machinery that dispenses money with calculated generosity to manufacture loyalty.

This is not politics as usual. It is power acquisition by financial saturation. And Ogun State must decide whether it will reward that model, or reject it outright. Ogun State must make a choice: leadership forged through genuine, organic consensus, or a governorship manufactured through financial muscle and Abuja-backed maneuvering. The difference is not cosmetic—it is foundational.

Yes, there is a legitimate argument that Ogun West deserves its turn at the governorship after Ogun East. But equity is about justice for a region, not an opportunity for political importation.

Rotational fairness should empower authentic sons and daughters of Ogun West who have labored within the state’s political ecosystem, not serve as a vehicle for an externally constructed ambition.

In summary, this debate is not personal; it is structural. It concerns political identity, state integrity, and the long-term direction of Ogun State. Ogun is not merely a governorship seat to be captured. It is a state with legacy, pride, and memory. Its leadership should emerge from within its soil, not be transplanted into it for strategic gain.

The decision before Ogun voters is simple: Should Ogun State reward calculated political relocation or protect the integrity of its own political evolution?

Let us be clear: Ogun State is not a political retirement plan. It is not a consolation prize for ambitions that collapsed elsewhere. And it is certainly not an annex of Lagos State. Senator Olamilekan Adeola built his entire political career in Lagos—nurtured in Alimosho, empowered by Lagos structures, and sustained by Lagos politics. When it became obvious that the governorship of Lagos was beyond reach, he did not suddenly “discover” Ogun. He relocated his ambition. Ogun was not a lifelong calling. It was Plan B. With deep pockets and federal connections, he crossed the border, planted political flags, assembled loyalists with financial inducements, and captured the Ogun West senatorial seat. Let us not romanticize it, this was not an organic uprising of the people. It was a calculated takeover.

The governorship is clearly the ultimate target. But Ogun State is not a bazaar where power goes to the highest spender or the most connected aspirant. This is the soil that produced Awolowo’s ideology, Ransome-Kuti’s defiance, Soyinka’s intellect, Solarin’s conscience, Abiola’s sacrifice, and Obasanjo’s force of will. It is the homeland of the Alake and the Awujale. Ogun’s political culture was forged in struggle, sharpened by ideas, and sustained by memory. Leadership here has never been defined by the size of a war chest or the strength of Abuja alliances.

Yes, Ogun West has a legitimate claim to produce the next governor. Rotational equity is a fair and defensible principle. But equity must not become an entry point for political transplantation.

Ogun West deserves leadership rooted in its own history, individuals who have grown within its communities, invested in its development, and shared its political journey long before the arithmetic of rotation made it attractive. This is about authenticity. It is about fidelity. It is aboutthose who stood with Ogun when there was no immediate prize, not those who arrived when the pathway cleared. If ambition-driven migration becomes the norm, Ogun State risks becoming a refuge for displaced political projects from Lagos. What is framed today as strategy could become tomorrow’s template. This coming gubernatorial election, therefore, transcends any single individual. It is about whether Ogun will defend the integrity of its political evolution or quietly permit its highestoffice to be captured by financial leverage and external influence.

Ogun is not a commodity. Its governorship is not a transferable title. And its future should not be negotiated like a transaction.

Muyiwa Sobo, Esq., writes from Abeokuta.

Leave a comment