Why Amnesty for Boko Haram, ISWAP and Bandits is a Risk Nigeria Cannot Afford

By Idowu Ephraim Faleye +2348132100608

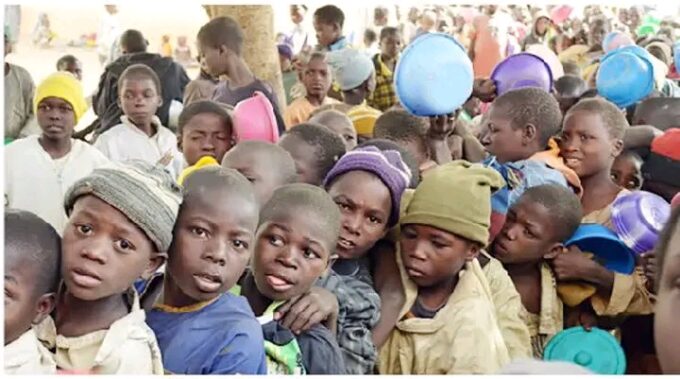

Nigeria is bleeding. Villages are emptied overnight, highways have become death zone, schools are shut because of Children kidnappings, mass graves are no longer shocking headlines, and military hospitals are littered with disabled soldiers. In the middle of this pain, some Northern leaders, speaking through Arewa platforms, are asking the country to grant amnesty to Boko Haram, ISWAP, bandits, and violent herdsmen.

To tired citizens and frightened communities, it sounds like hope and relief. But when you look closely, it is neither relief nor hope. It is a dangerous shortcut that risks turning Nigeria’s insecurity into a permanent condition.

It is natural for a nation exhausted by violence to crave quick peace. Amnesty feels like an easy door out of a burning house. But not every door leads to safety. Some lead deeper into danger. Granting amnesty without clarity about who the fighters are, where they come from, and what they are truly agitating for is not peacebuilding. It is gambling with national survival. Peace built on confusion does not last. It collapses and returns with greater force.

The first problem with the amnesty call is simple but critical: nobody has clearly defined who will benefit from it. Are these fighters Nigerian citizens? Are they foreigners? Are they criminals, ideological extremists, or displaced herders who turned violent? Are they all the same group, or different networks using the same weapons? These questions have not been answered, and that silence is alarming. Amnesty without identity is blind policy.

Supporters of amnesty often point to the Niger Delta and say, “It worked there, so it can work here.” This comparison is misleading. Niger Delta militants were largely Nigerian citizens from identifiable oil-producing communities. Their grievances were clear. Their land was polluted, their rivers destroyed, and their resources taken while they lived in poverty. Their struggle was local, traceable, and rooted in environmental injustice. The government knew who it was negotiating with and where reintegration would happen.

Northern Nigeria is a different reality. The violence there is not driven by one clear grievance. It is a mix of terrorism, banditry, kidnapping, cattle rustling, religious extremism, and cross-border crime. Many fighters move freely across Nigeria’s porous borders from Niger, Chad, Mali, and deeper into the Sahel. Climate pressure, insecurity, and long-standing transnational networks have pushed armed groups southward, and Nigeria has become a soft landing zone.

Many of these fighters have no documents. They use aliases. They blend into pastoral routes that existed long before modern borders. There is no reliable system to separate locals from foreigners. In this situation, amnesty risks doing something irreversible: turning foreign fighters into legal beneficiaries of the Nigerian state. What is presented as reconciliation could quietly become legalization of invasion.

This danger is made worse by ideology. Boko Haram and ISWAP are not confused groups seeking inclusion. They have been very clear about what they want. They reject Nigeria as a plural and democratic country. They reject Western education, freedom of belief, and constitutional governance. Their goal is not reform but domination. Their violence is not accidental; it is doctrinal. Amnesty does not erase ideology. It only pauses violence until conditions are favorable again.

History shows this clearly. Many fighters previously described as “repentant” returned to the forest. Some used negotiation periods to regroup, rearm, and recruit. When violence is rewarded without belief change and accountability, it becomes a business model. Others watching from across the border learn a simple lesson: enter Nigeria, cause havoc, and eventually you may be forgiven, paid, or settled.

There is also an uncomfortable truth Nigerians must confront honestly. A significant number of bandits, violent herdsmen, and even Boko Haram fighters are immigrants from the Sahel. This is not an attack on any ethnic group. Millions of Fulani Nigerians are peaceful citizens and victims of the same violence. But denying the transnational nature of the threat does not make it disappear. Many fighters operate within Fulani pastoralist networks that stretch across West and Central Africa. These networks are easily exploited by extremists and criminals.

When Arewa leaders push for amnesty without addressing border control, identity verification, and immigration, it raises serious questions. What happens when thousands of armed migrants are absorbed under the banner of peace? What happens to communities that lost land, farms, and families to these same fighters? Amnesty in this context risks normalizing violent settlement and inflaming ethnic and religious tensions that Nigeria is already struggling to manage.

The moral cost is also heavy. Amnesty is supposed to heal wounds, not deepen them. What does it say to victims when the state negotiates with those who killed their families while offering little justice or protection? What message does it send when terror appears to be a faster path to government attention than peaceful citizenship? Peace without justice breeds resentment, and resentment is fertile ground for future conflict.

Supporters of amnesty argue that military solutions have failed, and they are partly right. Guns alone cannot defeat ideology or organized crime. But admitting the limits of force does not automatically make amnesty the answer. There are other options that do not involve rewarding violence. Nigeria needs stronger borders, better intelligence sharing, serious regional cooperation, and protection for vulnerable communities. It needs deradicalization rooted in education and truth, not cash payments and political theater.

Reintegration, if it must happen at all, should be narrow, not blanket. It should apply only to verified Nigerian citizens with traceable identities and clear evidence of disengagement from violence. Even then, it must be strict, monitored, and transparent. What is being proposed by many Northern leaders is not careful reintegration. It is broad amnesty, and broad amnesty in a context of foreign infiltration and extremist ideology is reckless.

There is also a problem of consistency. When violence occurs in other parts of Nigeria, there is rarely talk of forgiveness or dialogue. Protesters are crushed. Self-defense groups are criminalized. Yet when armed groups kill thousands in the North, some leaders rush to call for negotiations. This double standard weakens national unity and deepens distrust. Peace cannot be built on selective justice.

Nigeria is not just fighting criminals in the forest. It is fighting a revolutionary extremist ideology. Any policy that ignores this reality is bound to fail. Amnesty does not change beliefs. It does not dismantle networks. It does not secure borders. It only delays the next wave of violence.

The real choice before Nigeria is not between war and peace. It is between real peace and temporary silence. Temporary silence can be bought. Real peace requires hard decisions, honesty, and courage. It requires protecting sovereignty, securing borders, exposing extremist ideology, and standing with victims, not appeasing their killers.

Granting amnesty to Boko Haram, ISWAP, bandits, and violent herdsmen without clarity, verification, and accountability is not compassion. It is surrender disguised as policy. Nigeria cannot afford that mistake. Not now, and not in the future.

©️ 2025 EphraimHill DataBlog

Leave a comment