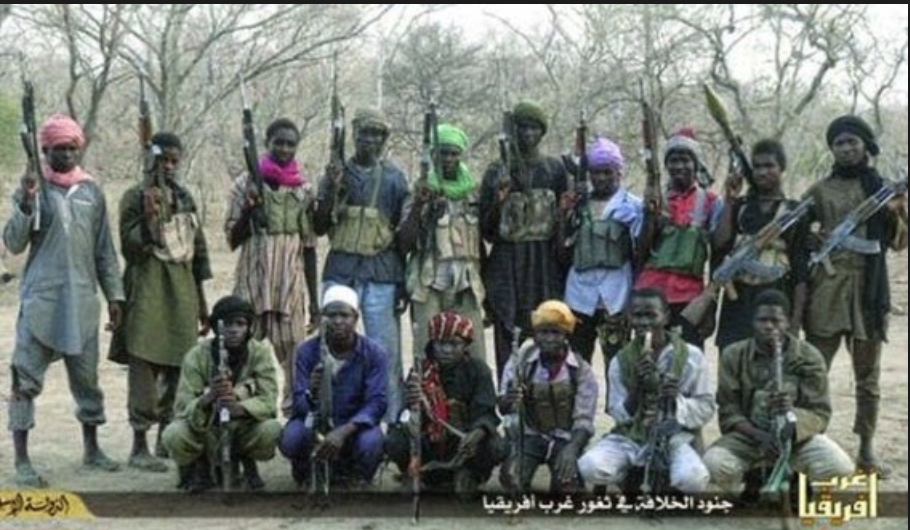

Boko Haram, ISWAP, and the Network of Silent Enablers: An Ideology at War with Freedom

By Idowu Ephraim Faleye +2348132100608

Many people still ask what Boko Haram and ISWAP are really fighting for in Nigeria. Some say it is poverty. Others say injustice, politics, bad leadership, or neglect of the North. These explanations sound comforting because they make the crisis feel simple and fixable. But they miss the core truth. They do not explain the scale of violence, the cruelty, or the audacity with which these groups destroy lives. If we are serious about understanding this war, we must be honest enough to say what many avoid saying. Boko Haram and ISWAP are not fighting for welfare or inclusion. They are fighting for an idea. And that idea is deeply hostile to freedom, coexistence, and Nigeria itself.

At the heart of Boko Haram and ISWAP is a political and religious doctrine that divides the world into believers and enemies. In this worldview, there is no middle ground. You either submit fully or you are treated as an obstacle. There is no room for choice, debate, or diversity. Faith is not something personal. It is something enforced. Violence is not a tragedy. It is a duty. War is not a last option. It is the main tool.

This way of thinking did not start in Nigeria, and it did not grow naturally from our many cultures. It is imported. It has roots in revolutionary Islamist ideologies that were clearly stated decades ago and then exported across borders. After the 1979 Iranian revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini openly described a vision built on conquest and domination. He spoke about exporting revolution to the whole world until one religious order ruled everywhere. He framed war as central to religion and described faith without war as weak. He presented killing unbelievers as a noble mission and obedience as something that must be achieved through the sword.

These were not careless words. They formed a doctrine. A doctrine that turned religion into state power and violence into virtue. A doctrine that rejected coexistence and declared permanent war on systems that allow freedom of thought. Boko Haram and ISWAP did not copy this ideology word for word, but they absorbed its spirit. Different accents, same message. Different terrain, same goal.

Once this is understood, many things become clearer. Boko Haram’s hatred of schools is not accidental. Education creates questions, and questions weaken blind obedience. Their attacks on churches reject religious plurality. Their attacks on mosques and Muslim leaders who disagree with them show that even within Islam, only one voice is allowed. Their terror against villages is not madness. It is strategy. Fear is how obedience is forced when consent is impossible.

This ideology does not believe people can be persuaded with reason. It believes people must be broken with violence. It teaches that the sword leads to paradise and that suffering inflicted in the name of faith is holy. When such ideas take root, human life loses value. Children become tools. Women become spoils. Communities become targets. Mercy becomes weakness.

Boko Haram and ISWAP are often described as insurgents, as if they are simply rebelling against the Nigerian state. That label is misleading. Insurgents usually want to replace a government or gain autonomy. These groups want more than that. They want to erase Nigeria as a plural nation. They reject the constitution, democracy, and the idea that people can choose their leaders or beliefs. Their aim is total control of life, thought, and behavior under a rigid order enforced by violence.

This is why negotiations based on grievances often fail. You cannot bargain with an ideology that sees compromise as sin. When fighters say they want Sharia, they do not mean moral guidance. They mean absolute power. Courts without appeal. Laws without consent. Punishments without mercy. A system where disagreement is criminal and silence is survival.

Wherever these groups gain control, the pattern is the same. People are jailed for small disagreements. Young men are executed for refusing to join. Women are forced into marriages. Minorities are crushed. Culture is erased. Music is banned. Learning is forbidden unless it serves the ideology. Life shrinks until fear fills everything.

What makes this tragedy worse is not only the fighters in the forest, but the system that quietly enables them. Over the years, evidence has continued to surface that radicalization is not limited to camps and villages. It has entered institutions. The report that some students of the University of Maiduguri were allegedly working for Boko Haram was a painful reminder. A university is meant to shape minds for progress, not violence. Yet, this did not happen overnight. These students were radicalized slowly, deliberately, and patiently. They were taught to see Boko Haram and ISWAP as righteous. This is how extremism works. It creeps in quietly, hides behind religion and grievance, and then captures the mind.

If it could happen in a university, it can happen elsewhere. That is the uncomfortable truth. We must ask how many institutions already have people who have absorbed this ideology. How many individuals sit in offices, wear uniforms, or hold influence while secretly believing in a violent worldview that is hostile to the Nigerian state. These are not easy questions, but they are necessary ones.

This is where the discussion becomes even more sensitive. Over time, a pattern has emerged where individuals, such as Sheikh Gumi or groups speak out to defend, excuse, or soften the actions of extremists. They frame mass murder as farmers-herders misunderstanding. They warn against “stigmatizing” killers while remaining silent about victims. Some of these voices are not neutral. Many echo the same ideological language used by global extremist movements. They present themselves as advocates of peace, but consistently shift blame away from the ideology and toward the state or society.

In extremist networks worldwide, such voices are often described as representatives, sympathizers, or useful allies. They may not carry guns, but they shape narratives. They provide cover. They raise funds. They influence opinion. In some cases, they are rewarded financially or politically for this role. This does not mean everyone who calls for dialogue is an extremist. But it does mean we must stop pretending that all defenders are innocent or detached from the agenda.

Radicalization inside institutions is not limited to universities. It becomes a national security nightmare when it reaches the military, intelligence agencies, immigration services, prisons, and the civil service. Information is power. When people who secretly support extremist causes have access to sensitive data, operations are compromised. Lives are lost. Ambushes happen. Trust collapses. Nigeria has seen too many cases where attacks raised serious questions about insider leaks.

This is not an accusation against institutions as a whole. Many Nigerians serve with courage and integrity. But even a few radicalized individuals can cause enormous damage. Modern conflict is not only fought with guns. It is fought with ideas, information, and influence.

There is also a broader historical layer that must be discussed carefully and honestly. Extremist groups do not operate in a vacuum. They often align themselves with long-standing narratives of dominance, expansion, and control that predate the Nigerian state. Across history, certain elite-driven agendas have used religion and identity to justify expansion and authority. These agendas were never about ordinary people. They were about power.

It is important to be clear here. No ethnic group is a single mind. No community shares one intention. Millions of Fulani, like millions of Nigerians from other groups, live peacefully, suffer from violence, and reject extremism. They are victims too. However, extremist movements have repeatedly drawn from historical narratives associated with Fulani-led jihads and conquest ideologies to legitimize their actions. Boko Haram and ISWAP did not invent these stories. They adopted and weaponized them.

In this sense, the fighters in the forest function as foot soldiers for a broader ideological project that benefits a small network of elites and global extremist movements. The foot soldiers die. The ideologues and sponsors hide behind institutions, politics, and activism. This pattern is not unique to Nigeria. It is seen in many conflicts where religion is used as cover for domination.

Understanding this does not mean blaming entire ethnic group. It means recognizing how history, ideology, and power intersect. It means refusing to allow extremists to hide behind identity. It means exposing how ordinary young people are recruited to die for agendas that are not truly theirs.

Nigeria is a country built on differences. Different religions. Different ethnic groups. Different cultures. This diversity is not a weakness. It is our strength. Any ideology that demands uniformity through force is at war with Nigeria itself. Boko Haram and ISWAP are not just fighting the government. They are fighting the idea that people can live together without killing each other over belief. They are fighting freedom of conscience.

This is why the response cannot be only military. Soldiers can push back fighters, but they cannot kill an idea. That requires clarity and courage. We must teach what this ideology really says, not what its defenders claim. We must separate personal faith from political domination. Faith freely chosen can inspire good. Faith enforced by the gun becomes tyranny.

We must also stop being afraid of plain speech. Rejecting extremist ideology is not an attack on Islam. It is a defense of humanity. Millions of Muslims worldwide reject this violent worldview and suffer under it. Silence allows extremists to claim ownership of faith. Speaking clearly takes it back.

The cost of denial is already visible. Regions traumatized. Children raised in fear. Communities displaced. Development stalled. The longer this ideology is allowed to hide inside institutions and narratives, the harder it becomes to uproot.

Nigeria stands at a crossroads. One path leads to excuses, appeasement, and endless bloodshed. The other leads to clarity, resistance, and renewal. Choosing clarity means admitting that Boko Haram and ISWAP are fighting for domination, not justice. It means strengthening institutions from within, and exposing, arresting and prosecuting ideological collaborators, no matter how respectable they appear.

This is not a war against a religion or a people. It is a war against an idea that turns belief into a weapon and declares permanent war on freedom. Nigeria must reject it fully, openly, and without apology. No nation can survive if it allows an ideology of violence to define its future.

*Disclaimer:*

This article examines extremist ideology, institutional infiltration, and historical narratives used by violent groups. It does not target any religion or ethnic community. The goal is to promote understanding, protect lives, and defend Nigeria’s plural society.

*©️ 2026 EphraimHill DataBlog*

Leave a comment