The 2026 Electoral Amendment Bill: Between Speculation and Constitutional Realities:

The brouhaha, drama, hysteria, and energy we are unleashing about the 2026 Electoral Amendment Bill are totally misplaced and premature. The law concerning the amendment of the 2022 Electoral Act has not yet been passed until the harmonisation committee—whose membership is drawn from both the Senate and the House of Representatives—sits together to collectively work out aspects of the two versions of the bill passed by both chambers of the National Assembly, deciding what should be included or struck off. All the ongoing hysteria about whether the Senate approved electronic transmission of results or even electronic voting is purely speculative and unfounded.

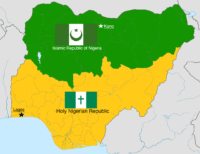

Before a bill becomes law in Nigeria, there must be concurrence between the Senate and the House of Representatives. Together, these two chambers constitute the National Assembly, as expressly provided under Section 47 of the 1999 Constitution of the Federal Republic of Nigeria (as amended), which states: “There shall be a National Assembly for the Federation which shall consist of a Senate and a House of Representatives.”

Furthermore, the legislative process is guided by Section 58 of the Constitution, which stipulates that a bill must be passed by both Houses of the National Assembly before it is presented to the President for assent. Specifically, Section 58(1) provides: “The power of the National Assembly to make laws shall be exercised by bills passed by both the Senate and the House of Representatives and, except as otherwise provided by this section, assented to by the President.”

Even when a bill is passed by both Houses, it is not yet Uhuru. For it to become law, the President must append his signature to it. Under Section 58(3), the President may withhold assent, effectively vetoing the bill. However, the Constitution empowers the National Assembly to override such a veto: Section 58(5) provides that if the President withholds assent and the bill is again passed by each House by a two-thirds majority, “the bill shall become law and the assent of the President shall not be required.”

Thus, until both chambers harmonize their positions and collectively approve the same version of the bill—and until the President either assents or the National Assembly overrides his veto—the 2026 Electoral Amendment Bill cannot attain the force of law. This constitutional requirement underscores the bicameral nature of Nigeria’s legislature and ensures that no single chamber or individual can unilaterally enact legislation.

That said, I welcome the energy and cacophony of voices we have heard about the bill. It demonstrates a high level of political consciousness among Nigerians, reflecting their keen interest in political developments that will influence and shape the 2027 general elections.

Conclusion:

The debate surrounding the 2026 Electoral Amendment Bill should be tempered with constitutional realities. Until due legislative and executive processes are completed, speculation remains premature. Yet, the public engagement it has sparked is a positive sign of Nigeria’s evolving democratic awareness.

@ Okoi Obono-Obla

Leave a comment