Rethinking Terrorism Detention and Justice Beyond Ordinary Prisons

By Idowu Ephraim Faleye +2348132100608

Every time news breaks that another military convoy has been attacked, another village raided, or another group of soldiers ambushed, Nigerians ask the same question: how many more lives must be lost before the country adopts a strategy that will handle captured insurgents in a way that will not create bigger problem for the future?

For more than a decade, Boko Haram and Islamic State West Africa Province have unleashed terror across Nigeria. Communities in the North-East have been destroyed. Farmers have abandoned their land. Children have lost parents. Women have become widows overnight. Soldiers have been buried without honor, yet the violence continues.

When citizens hear that insurgents are arrested and kept in correctional facilities, many feel anger instead of relief. They ask: what is the purpose of a correctional center? Is it not meant to reform and rehabilitate? And if reform is the goal, can hardened extremists who embraced violent ideology truly be reformed in ordinary prisons?

Correctional centers were built on a simple idea. A person commits an offense, society isolates the person, the system reforms the person, and then the person returns better. This works for petty criminals and first-time offenders. It works for people who made poor decisions under pressure.

But insurgency is different. Boko Haram and ISWAP are not ordinary criminal gangs. They are ideological movements with structure, loyalty, and long-term goals. Many members believe deeply in their cause. Some even believe that dying for that cause guarantees eternal reward. That mindset is not easy to reverse.

Before arrest, many of them lived in forests and remote territories under harsh conditions. They survived in the bush for years. Compared to that life, structured prison conditions with regular meals, shelter, and medical care may not feel like extreme punishment. Some citizens see it as a temporary pause rather than real accountability.

This perception fuels frustration. It becomes worse when people remember that these same groups have attacked fortified military bases in the past. They have overrun heavily guarded installations. So citizens ask: if they could overpower military facilities, what stops them from organizing inside prisons? What prevents them from planning escapes or coordinating with outside networks?

Radicalization inside prisons is another known problem globally. When ideologically driven detainees mix with frustrated or vulnerable inmates, influence spreads. Recruitment can happen quietly, through conversation and manipulation. If hardened extremists recruit others inside correctional centers, the prison system expands the threat instead of reducing it.

That is why many Nigerians argue that ordinary correctional facilities are not suitable for high-risk terrorist suspects. They believe there should be separate detention structures designed strictly for containment and maximum security.

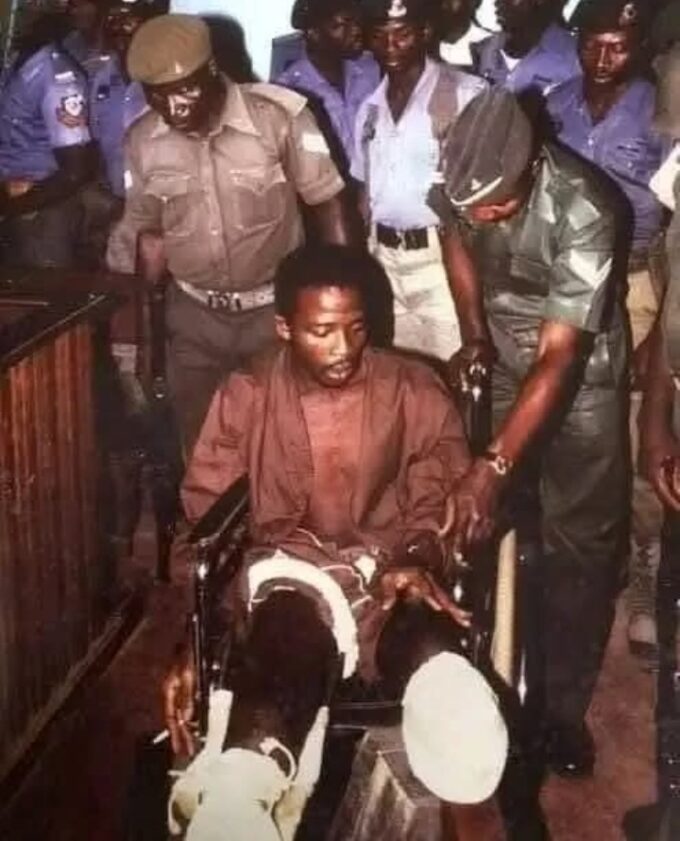

In this context, attention has turned to the former detention facility on Ita-Oko Island. Its strength was its geography. It could only be accessed by boat or helicopter. It was surrounded by dangerous waters infested with starved crocodiles and located far from cities and major roads. Such isolation reduces the risk of coordinated rescue attempts, limits communication with external networks, and protects surrounding communities from prison break dangers.

A regulated high-risk facility in a remote location could prevent extremist suspects from mixing with regular inmates. It could reduce the spread of radical ideology. It could strengthen operational control and limit external interference. However, If a remote high-security center is considered for detainees linked to Boko Haram or ISWAP, the aim should be stronger security, not hidden detention.

Terrorism-related cases should also be fast-tracked in the courts. Justice delayed creates frustration. When citizens see swift and firm legal processes, confidence increases. If Nigeria decides to establish a high-security detention facility in a remote location such as Ita-Oko Island, then it will also be wise to constitute a specialized terrorism court very close to that facility to handle cases involving Boko Haram, Islamic State West Africa Province and organized bandit networks.

A dedicated court structure near the detention center would reduce the security risks and heavy logistics involved in transporting high-risk suspects over long distances. It would limit exposure to rescue attempts, ambushes, or public disruption during movement. Such a court should be staffed with specially trained judges, prosecutors, and defense counsel who understand terrorism law, intelligence evidence, and national security procedures. This approach would combine strong security management with credible judicial process, ensuring that national protection and rule of law move side by side.

There is also the issue of cost. When taxpayers hear that individuals accused of mass killings are sustained under government budgets, many feel injustice. It feels like a double burden: communities suffer attacks, then public funds maintain the suspects.

Another concern is the risk faced by soldiers. In active combat, insurgents often shoot to kill. Soldiers defend themselves and protect civilians. Attempting to capture suspects alive during intense conflict can increase operational risk. Rules of engagement must balance intelligence needs with troop safety. Protecting those who defend the country should never be secondary.

Nigeria’s fight against Boko Haram and ISWAP is not only a military challenge. It is a test of governance, strategy, and resolve. Citizens are right to demand safety. They are right to question whether current systems are effective. They are right to expect serious consequences for those who kill innocent people.

*©️ 2026 EphraimHill DataBlog* Idowu Ephraim Faleye is a freelance writer promoting good governance and public service delivery +2348132100608

Leave a comment